1938 New England Hurricane: Looking Back at New England's Most Powerful Storm

- Tim Dennis

- Sep 21, 2023

- 13 min read

Every New England hurricane will forever be compared to this one hurricane. One of the region's most powerful and recognizable storms struck New England on September 21, 1938. This fateful storm formed off the African coast. Over the open ocean, the storm moved west-northwest. By the time the storm was north of Haiti and the Dominican Republic, it had strengthened to a category five hurricane with sustained winds of 160 miles per hour.

At this point, the storm began to turn north, away from Florida. The storm then began to make a familiar northeast turn. Countless hurricanes have been prevented from making landfall in New England due to this northeast track storms tend to take when paralleling the east coast. In this case, however, the northeast bend did not last long. When the storm was offshore of the Carolinas, the storm's track shifted due north.

Because a semi-permanent subtropical high pressure ridge in the Atlantic Ocean was abnormally far north, the storm was unable to move out to sea. As the storm moved northward, it began to weaken, but due to the storm's rapid forward movement, it did not have much time to weaken significantly.

The hurricane stayed well offshore of the entire east coast until it made landfall on Long Island as a category three storm with sustained winds of 120 miles per hour. The storm was moving at a speed of 50 to 60 miles per hour. The storm made a second landfall, this time in New England, after quickly moving over Long Island.

The storm made landfall near New Haven, Connecticut, as a category three storm with sustained winds of 115-120 mph. As it approached Vermont, the hurricane began to bend slightly to the north-northwest. Shortly after landfall, the hurricane became an extratropical storm. As it approached New York, the storm began to bend to the northwest. The storm passed into Canada and dissipated.

This hurricane was the deadliest, costliest, and most powerful in the database era, which began in 1851. Even before 1851, this hurricane was the strongest, with the 1815 gale being less powerful. The Great Colonial hurricane, with an estimated wind speed of 130mph, was the only hurricane that could potentially surpass this hurricane's mark. Of course, the wind speed of the Great Colonial has not been confirmed.

This storm truly was the "New England" hurricane, with major impacts in all six states. Here is a breakdown of the damage inflicted by each state, from surge to extreme winds to intense rainfall:

CONNECTICUT

The hurricane hit Connecticut at 4 p.m. on September 21, 1938, making landfall just east of New Haven. Weather forecasting was a mere shadow of what it is today in the early 1900s. As a result, the hurricane made landfall in New England with little warning, leaving residents scrambling to save their lives and property.

The storm surge in New Haven was measured at 10.5 feet, which is still a record. Other Connecticut cities had even higher totals, with Bridgeport nearing 13 feet and Stamford just over 14 feet. The surge, combined with winds of more than 100 miles per hour, destroyed coastal towns across the state. The surge pushed up the Connecticut River, completely submerging many towns along the river, particularly Hartford and Middletown.

Thirty cottages were destroyed along the shore in Fairfield alone. At least fifty people were evacuated from the city on boats, which were used to rescue people from flooded homes and transport them to higher ground. Rescuers waded into deep, cold water to pull evacuees out of the water and to safety. According to the Fairfield News:

“Meadows turned into a huge lake, not only the highway but even fences disappeared from sight and lashing waves threw angry white caps with terrific force a quarter mile from the beach and kept advancing rapidly.”

Along with the flooding and wind, large fires erupted across New Haven. According to New London:

“A few large vessels were blown ashore, one causing a fire when its galley stove upset. Brick buildings reduced to piles of rubble. Trees laid down in a row. Many large trees with good root systems snapped off.”

After a factory in the town had its roof blown off, floodwaters and fires destroyed the rest of the building. Many factories closed permanently after the hurricane, as many were still struggling to recover from the Great Depression.

Back in New London, where the storm's eye passed very close by, total devastation was seen. The fact that the area was experiencing astronomical high tides at the time of the storm added to the record-breaking storm surge. According to the city:

“Beach front cottages ruined, ripped open, moved off of foundations, caved in, or entirely washed away by wave action. Boats washed inland.”

A train (dubbed the Bostonian) became stranded on the tracks in Stonington due to debris. The power of the hurricane quickly overtook the train. Hurricane force winds began to batter the train, and flood waters rose around it. Some of the 275 people on board at the time saw full houses floating by the train. Two people attempted to flee the train at one point, but were washed away by the floods, presumably drowning. Fortunately, many on board were rescued.

The week before the hurricane, New England had received several inches of rain. The hurricane dumped another five to ten inches of rain. The extremely saturated ground made it that much easier for wind gusts exceeding 160 mph to bring down an unfathomable number of trees. Homes, vehicles, and power lines were all destroyed by falling trees.

Stanley Moroch, of Colchester, told of riding on a school bus with two other students. A tree fell in front of the bus, obstructing its path. A tree fell quickly behind the school bus, trapping it. The bus driver and the three students got off the bus and ran to Stanley's house, where they took refuge. When the storm died down, the other two students and the bus driver ran home.

The hurricane was moving north at breakneck speed, allowing it to exit as quickly as it entered. By the evening, conditions in Connecticut had improved, but damage had continued. The fires in New London raged all night.

RHODE ISLAND

The storm surge hit Rhode Island even harder than it did Connecticut. Rhode Island lacks the barrier that is Long Island to protect its coast. On top of this, Rhode Island was on the east side of the storm, leading to an onshore flow. Surges of 12 to 15 feet were reported in Narragansett Bay. A 20-foot surge was recorded in some areas of Rhode Island. Many people were swept away in an hour because they were unaware of the approaching storm. According to Providence:

“The new bridge was wrecked, highways and docks were blocked, the roof of the New Haven RR's big Union Station blew off, and hundreds of buildings suffered severe damage or were totally destroyed.”

Watch Hill in extreme western Rhode Island may have taken the brunt of the storm surge. This town is one of two that reported a 25-foot storm surge (the 25 foot mark was likely waves on top of the surge). At the time of the hurricane, Napatree Point, a village within Watch Hill, was home to approximately forty families. All of the houses in this area were destroyed. This neighborhood was never rebuilt. Today, the area is a wildlife refuge.

Storm surge damage in Barrington and Conimicut

Like in Connecticut, entire coastal communities were destroyed along the Rhode Island coast as a result of the combination of surge and high winds. Almost every structure on the state's coast was destroyed. In addition to being flooded by a 13-foot surge, Providence was battered by sustained winds of 100 mph with gusts reaching 125 mph. Winds were similar on Block Island. While the east side of the storm received the most wind, it did not receive nearly as much rain as the west side.

Rhode Island was home to the majority of the 700 or so deaths in New England. In Westerly alone, at least 100 people were killed. Bodies washed up on the beach weeks after the storm. Westerly High School was briefly transformed into a morgue. According to Bill Cawley of Washington DC’s Evening Star:

“I reached the outside world today after witnessing the scenes of horror and desolation that came in the hours after a tidal wave, hurled miles inland by a hurricane, engulfed Westerly, Rhode Island, my home, two days ago…I counted bodies, row upon sickening row of them…”

Several lighthouses were washed away, taking the lives of the keepers and their families. A school bus was blown into Mackerel Cove in Jamestown, killing several children. People were completely caught off guard because the storm struck without warning. Falling trees, power poles, and other flying debris killed many people.

Newport experienced some of the highest surges in New England, with up to 25 feet reported:

“The tidal wave which rose to a height of 25 feet and struck this island without warning Wednesday afternoon, demolished 500 homes at Island Park alone. It flattened 8000 of Newport's most beautiful trees. It scattered boats and yachts around the streets, destroyed three famous beaches, one amusement resort, and poured salt water into the Newport reservoir.”

Some houses were said to float up to two miles inland. A house in Charlestown was swept across the street, according to legend. This house is said to have stood across the street, where the storm had deposited it, until it was demolished in 2011.

Power was out for several weeks in parts of Rhode Island that weren't completely destroyed. This storm may have caused the most damage in Rhode Island.

MASSACHUSETTS

The storm surge and wind effects in Massachusetts were similar to those seen in Connecticut and Rhode Island. The storm had a significant impact across the entire state, but it was by far the worst in the southeastern part of the state.

The storm surge was not as severe as what Connecticut and Rhode Island experienced, but it was still noteworthy and powerful enough to have serious consequences. Buzzards Bay rose eight to fifteen feet overall. The surge wrapped all the way around Cape Cod, with Truro reporting eight feet. In New Bedford, which also experienced an eight-foot surge, up to two-thirds of all boats in the harbor sank.

This surge, like the previous two states, washed away homes, buildings, and boats along the coast. A 15-foot tide was reported in Bourne. A house in Bourne was "hurled" into the Cape Cod Canal, killing five people. Woods Hole, on the southwestern tip of Falmouth, reported:

“...water overtook homes in less than 5 minutes. A 250 ft. bathhouse at the Woods Hole beach was carried the length of a city block inland and lodged in the front yard of a cottage. Yachts were torn from their moorings. The town bathing pavilion at Old Silver beach was reduced to splinters.”

Almost all power lines were downed in the Cape Cod area, and gas was leaking from broken lines. All transportation in the area was cut off, isolating the beleaguered residents.

Extreme winds also made an appearance in Massachusetts. The Blue Hill Observatory recorded sustained winds of 121 mph, with a maximum gust reaching 186 mph. According to Blue Hill, the strongest wind gust ever recorded from a hurricane is 186mph. The wind carried a car thirty feet from the road and tossed it into Salt Pond in Falmouth. The wind blew down houses, severely damaged hospitals and other structures, and felled countless trees.

Another major issue that Massachusetts residents faced was excessive rainfall, particularly in the state's western region. The hurricane's center entered Massachusetts near the Connecticut River and followed the river northward. In western Massachusetts, up to six inches of rain fell, on top of several inches that had fallen in the week preceding the hurricane's arrival.

The river in Springfield rose up to ten feet above flood stage, causing widespread damage throughout the city. Residents in Ware were stranded after flooding cut off the town. Food and medicine had to be air dropped into town for several days after the storm. Main Street was basically gone when the water receded.

Boston was also hit hard. Winds topped out near 90 mph, with gusts approaching 100 mph. According to the city:

“A section of a falling roof critically injured a woman. A section of the roof in the maternity building of the hospital was carried away…Cars found their passage blocked at every turn by fallen trees and piles of debris. Plate glass windows were smashed everywhere. A section of metal cornice from a roof was blown off of a woman's house in the Back Bay region of Boston…The Boston waterfront was badly lashed. The USS Constitution was found listing badly…Downtown, pebbles flew from rooftops hitting pedestrians on the streets.”

The storm lashed Cape Ann to the north. A fifty-foot wave was reported off the coast of Gloucester, the highest wave height recorded during this storm. Wind and trees destroyed or unroofed cottages in Amesbury, in the state's northeast corner. Nearly all roads in Haverhill, which is in the same area as Amesbury, were blocked by trees, power lines, and poles. Rain caused street flooding at Lowell and Methuen, once again in the northeast corner. Newburyport, on Essex County's coast, reported:

“Smashed rooftops, flattened piazzas and fences, damaged church steeples, and hundreds of broken windows in business blocks bore evidence of the passage of the hurricane.”

As in Connecticut and Rhode Island, the hurricane blew out as quickly as it came in, with nearly all damage reported within five hours.

VERMONT

The storm moved into western Vermont in the evening. The hurricane had officially become an extratropical storm by this point, but it was still powerful, packing hurricane-force winds.

At the same time, the storm began to turn west after traveling due north through southern New England. Even though the storm had lost its tropical characteristics, there were reports of calm conditions and even clearing in the storm's center as it passed through southern Vermont.

The 1938 hurricane is still considered one of Vermont's worst windstorms. Wind gusts of 80 to 100 mph were reported. 100 mile an hour gusts is equivalent to a category two hurricane. St. Johnsbury's northeast corner saw downed trees and wires, as well as damaged roofs and toppled chimneys. Northern Vermont said:

“Practically all of northern VT is isolated from the outside world. Homes were damaged and fruit and sugar orchards flattened by the hurricane.”

Along with the wind, massive flooding occurred across the state. Dams and bridges were washed away in Brandon, in the state's west-central region. Flooding and wind damage cut off residents in Rutland. A Delaware & Hudson trail was derailed in Castleton, located west of the Green Mountain National Forest, when it encountered broken tracks caused by floods.

A farmer was stopped in his tracks while working in his fields. He claimed to be able to smell the ocean. Similarly, salt spray was seen on windows in Montpelier. Montpelier is 120 miles from the nearest coastline. When a tree crashed through the walls of Montpelier's Playhouse Theater, two people were injured.

The storm had passed over Lake Champlain by 8:00 p.m. Around 8:30 p.m., the storm passed through Burlington. The storm then made its way into New York and, eventually, Canada. Five people were killed in the state in total.

NEW HAMPSHIRE

Despite the fact that the storm passed far to the west of New Hampshire, the state suffered significant damage. While the state was spared significant rainfall, its location on the east side provided it with damaging winds. The storm's headline in New Hampshire was the destruction of the state's forests. A total of 1.5 billion board feet of timber were felled across the state. It would take years to recover the storm-damaged timber. Fallen logs were dumped in Turkey Pond in Concord to aid in rebuilding efforts. Floating logs covered the entire pond. According to Concord:

“Many of Concord's streets were blocked by uprooted trees. Hotline Park practically ceased to exist. Pine trees that had stood for many years were either uprooted or broken and this practically wiped out an historic forest known as Old Pine Woods. Fully half of the famous elm trees in the State House yard were blown down. The fragments of the roof of a garage struck a man causing an injury leading to his death.”

In New Hampshire, the wind was also strong enough to cause structural damage. Barns were blown down in Bow, near Concord, killing two people. Manchester suffered significant wind damage. According to the city:

“A brick wall the entire length of the third story crumpled and caused the roof to cave in. The shoe factory lost the windows on one side. The cemetery resembled a desert waste as scores of choice trees and large areas of shrubbery were destroyed. Several hundred dwellings in the area lost roofs and porches were stripped of slate.”

New Hampshire’s other large city, Nashua, saw significant wind damage. That city reported:

“A man was killed when struck by a falling tree, another when a flying missile struck him on the head. Others were injured by falling signs, trees and debris. The roof of a factory was torn off and sailed over 300 feet crashing through the rear of an Auto Fender shop tearing a hole big enough to drive a truck through.”

Milford, in south central New Hampshire, suffered significant damage as well. The wind ripped apart a house in town, as well as a damaged steeple and shattered stained glass window. It was claimed that all rural roads were impassable.

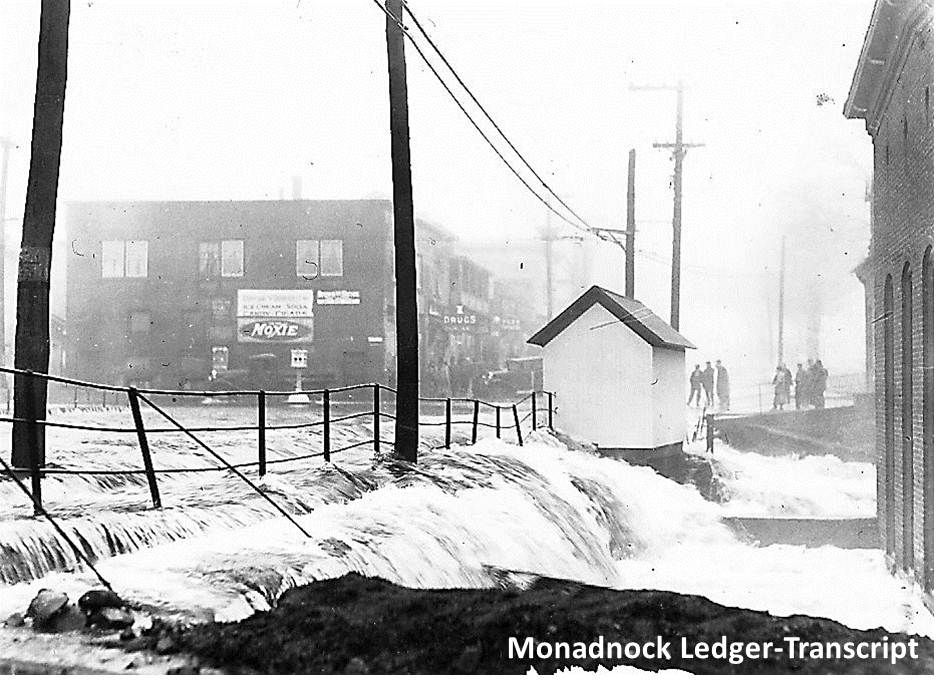

Between Keene and Nashua, Peterborough may have been the hardest hit town in the state. A fire destroyed several downtown buildings. Because of the flooding of the Contoocook River, firefighters were unable to reach the fire. The town was completely cut off and could only be reached by plane.

While rainfall was not nearly as heavy as in other states, flooding occurred throughout the state. Several rivers have burst their banks. The Contoocook and Suncook rivers both flooded nearby towns of Hopkinton and Pembroke. Flooding caused the destruction of a bridge in Jaffery.

Storm surge was mostly minimal along New Hampshire's eighteen-mile coast. One wave crashed into Portsmouth, destroying many cottages. Aside from that, no mention of coastal damage was made. Unlike many other storms, the worst of the damage occurred inland.

Mt. Washington experienced a maximum wind gust of 163 mph. By early evening, the storm had passed. In New Hampshire, a total of 13 people were killed.

MAINE

Because Maine was the furthest away from the storm, the damage was not nearly as severe as in the other five New England states. Having said that, the state still suffered significant consequences. Maine, like the rest of northern New England, felt the brunt of the storm in the early evening.

The "twin cities" of Lewiston and Auburn, north of Portland, bore the brunt of the damage in Maine. The first report of damage was of a sign flying across the street from a Lewiston music hall and crushing a car. At some point, every street in the cities was blocked by trees. Maine, like the other five states, saw numerous trees fall to the ground. Trees were seen being 'flung' across highways in Alfred, in the state's southwest.

Despite winds that remained below hurricane force, there was structural damage across the state. Houses had their roofs blown off and their windows blown out. Back in Lewiston, a skylight blew off a roof, sending three people fleeing as it crashed to the ground. The Lewiston Daily Sun simply said:

“Worst windstorm in the two cities history.”

Being so far east of the track kept the rain largely out of Maine. There was no rain along the coast and only a light drizzle inland. However, the Penobscot River overflowed its banks in Bangor due to rains that fell in the week preceding the storm. This storm's light rain was the final straw for the river.

Maximum winds in Portland reached 70 mph, just shy of hurricane force. The city escaped with only minor damage. According to the city:

“Except for wire damage and ruined boats on the waterfront, Portland escaped with comparatively little damage.”

Maine, like New Hampshire, experienced very little storm surge. By 9:00 p.m., the storm in Maine was nearly over.

By the time the storm passed through New England, it had permanently altered the landscape. In the few hours it took for the storm to pass, approximately two billion trees were destroyed. According to reports, the hurricane destroyed one out of every three trees in New England.

Approximately 8,900 buildings and homes were damaged, towns were destroyed, and villages were irrevocably damaged. Storm damage could be seen for decades after the storm. The storm's aftermath can still be seen throughout the region today.

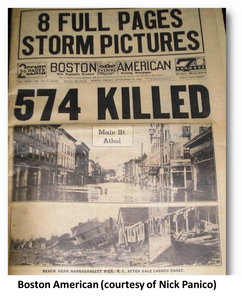

In 1938, storm damage exceeded $300 million. Around 700 people were killed in New England by the storm. Only Maine did not see a single loss of life. The Great New England Hurricane (also known as the 'Long Island Express') truly was 'the big one'.

Kommentare